One of the best parts of undertaking an interventive treatment on an object is researching its history and finding out how it relates to the broader context of the collection its housed in. While working on this Roman glass beaker in the lab, I discovered its interesting role in the invention of glass blowing techniques and how this object connects us to other museums around the world. There will be a follow-up blog post about this treatment.

This 1st century glass beaker, (fig. 1), from Marion, Cyprus came to The Fitzwilliam Museum in 1876 from Luigi Palma di Cesnola, an amateur archaeologist, solider, and the first director of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The MET) from 1879 to 1904[1]British Museum. n.d. Luigi Palma di Cesnola. [online] Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG61173 [Accessed 12 May 2022].. Luigi was born in Turin, Italy and after immigrating to America, he joined the Union army in the Civil war[2]British Museum. n.d. Luigi Palma di Cesnola. [online] Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG61173 [Accessed 12 May 2022].. After rising to the rank of Brigadier General, he went to Cyprus as an American consul and took up archaeology as a hobby[3]British Museum. n.d. Luigi Palma di Cesnola. [online] Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG61173 [Accessed 12 May 2022].. When he returned to America, he brought 35,000 objects back with him, the largest body of archaeological material ever removed from Cyprus[4]Barker, C, and R Merrillees. 2017. “Cypriot Antiquities From The Cesnola Collections In The Nicholson Museum At The University Of Sydney”. Mediterranean Archaeology, no. 30: 51-72. In 1879, he was appointed director of The MET after he sold the majority of his finds to the museum[5]Barker, C, and R Merrillees. 2017. “Cypriot Antiquities From The Cesnola Collections In The Nicholson Museum At The University Of Sydney”. Mediterranean Archaeology, no. 30: 51-72. Cesnola sold this beaker to The Fitzwilliam Museum in 1876 and it’s been in our collection ever since.

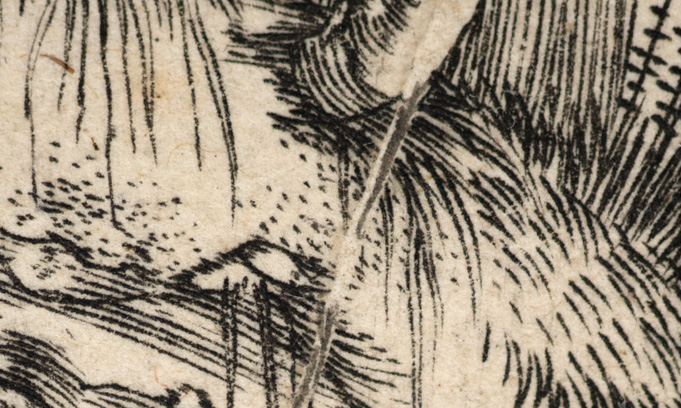

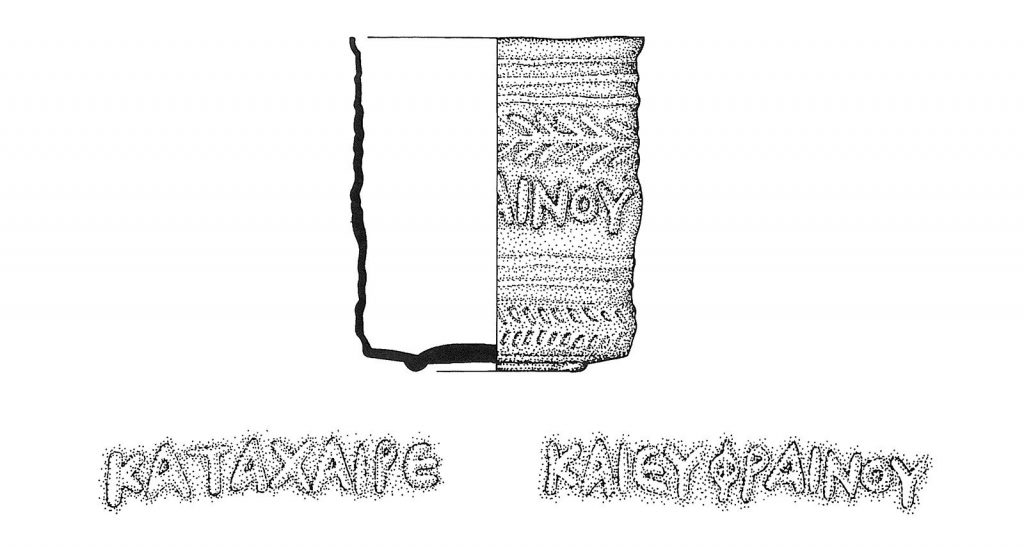

While fragmentary, this glass beaker is dazzling. It was made with a three-piece mould, an invention that is attributed to an artist and workshop owner named Ennion[6]Corning Museum of Glass. 2015. Ennion and His Legacy: Mold-Blown Glass from Ancient Rome. Available at: https://www.cmog.org/article/ennion-and-his-legacy-mold-blown-glass-ancient-rome [Accessed 12 … Continue reading. He is the only artist of the time to sign his work, as seen in figure 3. While this particular beaker does not have Ennion’s signature, it is considered to be Ennion glass based on the fact it was mould made. The vertical palm fronds cover the three mould seams, making the piece appear seamless(fig. 2). In between the horizontal palm fronds, raised Greek inscription ‘KATAXAIPE KAI EYΦPAINOY’, which can be translated as ‘rejoice and be merry’. Cups like this one were used to serve wine and scholars believe that they were served to guests, hence the cheerful sentiments they convey[7]Wight, K. 2015. Souvenirs and Mold-Blown Glass For the Marketplace. Corning Museum of Glass. Available at: https://blog.cmog.org/2015/12/28/souvenirs-and-mold-blown-glass-for-the-marketplace/ … Continue reading.

Several of these glasses are known to exist in museum collections and are collectively known as the ‘Katakaire’ beakers because of their inscriptions. Two are found in The Corning Museum of Glass, with other examples in The Getty, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the Stroganov Collection, The MET (59.11.4), the de Clercq Collection, which was gifted by the Lourve in 1967, one in the British Museum (fig. 4). Several others have been recorded documented in the archaeological record, such as one from Agios Fotios, a village in Cyprus, and one in Edinburgh[8]Lightfoot, C. 2017). The Cesnola Collection of Cypriot Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. P. 52.. D. B. Harden, archaeologist and former director of the Museum of London, published Romano-Syrian mould blown glasses that were excavated from a first century tomb group in Yahmour, Syria[9]Harden, D.B. 1944-45. Two Tomb-Groups of the First Century A.D. from Yahmour, Syria, and a Sipplement to the List of Romano-Syrian Glasses with Mould-Blown Inscriptions. Syria, 24(1/1), 81-95..Four of these objects were Katakaire glasses, which were a part of The National Museum of Beirut’s collections[10]Harden, D.B. 1944-45. Two Tomb-Groups of the First Century A.D. from Yahmour, Syria, and a Sipplement to the List of Romano-Syrian Glasses with Mould-Blown Inscriptions. Syria, 24(1/1), 81-95.

Harden states in another publication that there are twenty known katakaire glasses found in archaeological excavations[11]Harden, D.B. 1935. Romano-Syrian Glasses with Mould-Blown Inscriptions. The Journal of Roman Studies, 25, 163-186. Available at: … Continue reading. It was difficult to track down the rest of these beakers, but some of the best examples can be seen in figure 4.

While over half of the examples listed come from Cyprus, it is uncertain if the glass workshop was located there. What is interesting about these beakers and Ennion’s moulded glass in general is that the inscriptions are in Greek rather than Latin. This led scholars to believe that Ennion worked in a region where Greek was commonly spoken over Latin, such as along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean sea[12]Corning Museum of Glass. 2015. Ennion and His Legacy: Mold-Blown Glass from Ancient Rome. Available at: https://www.cmog.org/article/ennion-and-his-legacy-mold-blown-glass-ancient-rome [Accessed 12 … Continue reading. Wherever the beakers were manufactured, they are an example of serial production in the ancient Roman world. With many examples of different households across the Roman Empire owning this same glass, these beakers are the ancient equivalent of purchasing glassware at your local John Lewis.

While The Fitzwilliam’s katakaire glass is not as complete as some of the other examples found in museums across the world, its history and importance is not lost in its fragmentary state. My hope is that through conservation and research, this beaker will be more easily interpreted and appreciated. Check back soon for part two of this post discussing the conservation process.

References

| ↑1, ↑2, ↑3 | British Museum. n.d. Luigi Palma di Cesnola. [online] Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG61173 [Accessed 12 May 2022]. |

|---|---|

| ↑4, ↑5 | Barker, C, and R Merrillees. 2017. “Cypriot Antiquities From The Cesnola Collections In The Nicholson Museum At The University Of Sydney”. Mediterranean Archaeology, no. 30: 51-72 |

| ↑6, ↑12 | Corning Museum of Glass. 2015. Ennion and His Legacy: Mold-Blown Glass from Ancient Rome. Available at: https://www.cmog.org/article/ennion-and-his-legacy-mold-blown-glass-ancient-rome [Accessed 12 May 2022]. |

| ↑7 | Wight, K. 2015. Souvenirs and Mold-Blown Glass For the Marketplace. Corning Museum of Glass. Available at: https://blog.cmog.org/2015/12/28/souvenirs-and-mold-blown-glass-for-the-marketplace/ [Accessed 12 May 2022]. |

| ↑8 | Lightfoot, C. 2017). The Cesnola Collection of Cypriot Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. P. 52. |

| ↑9, ↑10 | Harden, D.B. 1944-45. Two Tomb-Groups of the First Century A.D. from Yahmour, Syria, and a Sipplement to the List of Romano-Syrian Glasses with Mould-Blown Inscriptions. Syria, 24(1/1), 81-95. |

| ↑11 | Harden, D.B. 1935. Romano-Syrian Glasses with Mould-Blown Inscriptions. The Journal of Roman Studies, 25, 163-186. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/296597.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ae98ac19618268de8537609b00674987d&ab_segments=&origin= [Accessed 12 May 2022]. |