The Conservation Project

Fans are complex, three-dimensional objects made of several types of material. Conservation of fans from the recently acquired Lennox-Boyd collection has been a rewarding collaboration between conservators in the Applied Arts department and the Paintings, Drawings and Prints (PDP) department. Phase 1 of the project involved a condition survey, photography and treatment of a small sample of fans. Phase 2 involved a re-housing project, scientific analyses and conservation treatment in preparation for the current display at the Fitzwilliam Museum. A selection of 51 fans was made for the display, reflecting the variety in age, manufacture and condition of the Lennox-Boyd collection. This post discusses the project from a Paper Conservator’s perspective.

Paper Fans – Conditions

Although fan leaves can be made of materials such as vellum, bone and silk, the predominant material used is paper. The Lennox-Boyd collection contains over 400 paper–based folding fans and flat paper leaves. Of all the components that make up a fan, it is the leaf which suffers the most damage and deterioration. The quality and condition of fans in the Lennox-Boyd collection reflects their wide-ranging variety, age and history. Many fans show signs of ownership and long use: accumulated dirt and assorted tears and splitting along the pleats are the most common types of damage. Additionally, fans can be harmed by exposure to light, fluctuating temperature and humidity, pollution, biological attack from mould and insects, and contact with other, frequently inferior quality, materials. These affect the paper as well as the applied, painted or printed media which decorate the leaves.

Early European papers used for fans were hand-made from plant fibres, which were strong and long-lasting. There are many fine examples of these beautiful papers in the collection. With the advent of machine-made papers from around 1860, paper quality became more variable. Around this time, less durable, mass-produced papers started to appear in fans. Over time, these poorer-quality papers become acidic and weak, tearing easily and losing their ability to endure opening and closing. Other materials used in fan manufacture have also developed and changed, often affecting the stability and permanence of the fan overall: adhesives may discolour and fail as they age; paints and printing inks become less permanent. Other fan components may affect the stability of the paper: the wooden or card ‘ribs’ which hold the fan leaf in place sometimes cause staining and degradation, as do corrosive or degrading paints and inks. The collection also exhibits a wide range of old repairs using materials such as stamp hinges, paper, thread, and pressure-sensitive tapes. Many of these repairs are unsightly and have caused further deterioration.

Conservation of Paper Folding Fans and Fan Leaves

Treatments undertaken on the Lennox-Boyd fans in preparation for display ranged from minimal cleaning to more interventive, labour-intensive repairs. Treatment of the folding fans was limited to actions such as gentle surface cleaning and physical repairs which could be carried out safely without taking the fans apart. The fans were supported underneath during treatment with tapering pieces of polyethylene foam and care was taken to apply as little pressure as possible to their delicate surfaces.

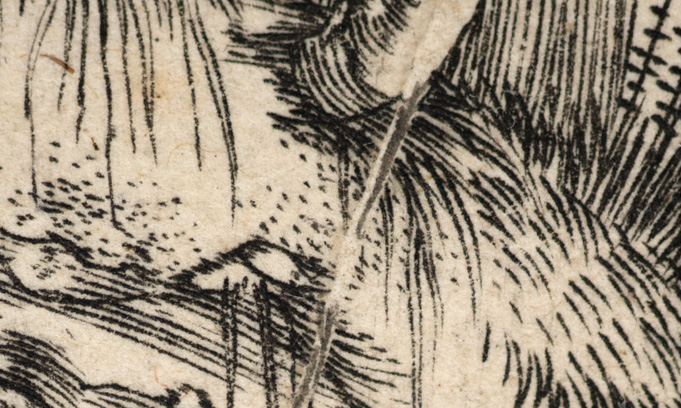

Dirt and dust were removed using soft brushes, accretions were carefully picked off using the tip of a scalpel blade, and the more ingrained dirt was reduced using either dry cleaning sponges or small wedges of vinyl eraser. Cleaning was avoided in areas with fragile media. Where possible, flaking or cracked paints were consolidated with a cellulose-based adhesive. Mould spores were safely removed using a brush and suction. Many flat fan leaves were detached from unsuitable acidic boards. Several discoloured and stained leaves were dry-cleaned, then washed in buffered de-ionised water. Before pressing they were given a coat of dilute gelatine to replace degraded sizing and gently re-adhere the sheets together where they had separated. They were then lightly humidified and pressed between blotters and weighted boards. Some disfiguring stains on the fan leaves were locally treated with a weak bleach solution and then rinsed.

Splits and tears were mended with starch paste and/or a cellulose-based adhesive and narrow strips of cut or torn Japanese tissue tinted with dilute washes of acrylic paint. Where possible, the two paper sheets making up many fan leaves was gently prized apart in order to insert the mend between the layers. The sheets were then pasted closed again to make the repair invisible. If this wasn’t possible, a small strip of tinted tissue paper was pasted along the reverse side of the damaged seam. Repairs were held in place to dry under small weights, using clamps or by hand, depending on the location of the damage and the strength of the paper. Losses were filled with Japanese paper of a matching weight, texture and colour. Disfiguring or damaging old repairs were removed and replaced.

Conservation procedures followed strict professional protocol, using conservation-grade materials, testing prior to treatments, and thorough documentation throughout.

Display and Storage of the Fan Collection

After treatment, a customized acrylic stand was made for each fan by technicians in the Applied Arts department. The stands can be tilted at different angles by means of a ball-joint mounting and are sensitively designed to support the open fan safely whilst on display. Flat fan leaves were hinged onto acid-free museum board with Japanese paper and starch paste, and given fan-shaped window mounts. Other fan leaves will be stored in polyester sleeves with acid-free card support. The majority of folding fans will be stored closed and wrapped in acid-free tissue. All the fans will be stored in museum Solander boxes on racks of dedicated shelving. It is hoped that the conservation of the Lennox-Boyd collection will continue, enabling more of these intriguing objects to be available for study and display in the future.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the curatorial and conservation staff in the Applied Arts department and the Paintings, Drawings and Prints department of the Fitzwilliam Museum. The fan collection of the late Hon. Christopher Lennox-Boyd (1941–2012) was accepted in lieu of Inheritance Tax by H M Government and allocated to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 2015. This conservation project was generously funded by the Marlay Group.