When Fashion Transforms the Truth

Gwendoline Lemée

January 2, 2018

Manuscripts and Printed Books

Tags: collage, conservation science, fragments, historical context, iconography, illuminated manuscripts, parchment, spectral imaging, truth

As part of Cambridge’s Festival of Ideas 2017, I took part in a series of behind-the-scenes talks on how we investigate the ‘true’ nature of museum objects. As the event was so successful and attendees showed a lot of interest in the subject, this blog post is aiming to share the story of the objects I discussed on that occasion.

What secrets or lies can we unveil, by which means can we do that, and how far can we go into our understanding of past practices? Some objects lead us into exciting journeys and this is the case of two manuscripts fragments from our collection (MSS 293a and 293b).

These two beautiful and quite peculiar illuminated fragments come from the Royal Monastery of St Thomas in Avila, Spain, and were presented by the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1918. By taking different approaches – those of a curator, a conservator and a research scientist – to investigate the truth of these objects, we can retrace their story and reveal some of their secrets.

Historical context and iconography

The description of the image is the first step in our investigation and already gives a lot of information. First we can see that the main part of each image is a large letter: we can identify an ‘M’ and a ‘D’. These are enclosed within composite floral borders containing birds, animals and grotesques, as well as the arms of Castile and Aragon and the devices of the Spanish sovereigns Ferdinand and Isabella, the yoke and the bundle of arrows respectively.

Questions arise already and we start wondering what text these two initials introduced, from which manuscript(s) the images were excised, and what is their context. The catalogue description suggests that the initial ‘M’ would have introduced Psalm 131 (the first psalm for Thursday Vespers) and the initial ‘D’ would have introduced Psalm 114 (the first psalm for Monday Vespers). This type of initial, “shaped and surrounded by densely populated foliage on highly burnished gold grounds, contained within frames inscribed with phrases from the accompanying text”, is, according to our curator Dr Stella Panayotova, “representative of Castilian illumination of the last quarter of the fifteen century which agrees with the internal evidence of the royal arms and devices.” The presence of the arms of Castile and Aragon as well as Ferdinand and Isabella’s devices does indeed give us a lot of information about the time of creation of these images. The two kingdoms of Castile and Aragon were united by this royal couple in 1479; in 1492, the pomegranate (not present here) was added to the royal arms to mark the conquest of Granada. We can therefore conclude that these images were created between 1479 and 1492.

Looking more carefully, we notice the strange layout of the borders. We can see that some of the animals are upside down and some of the drawings are incomplete. We are also aware that this sort of image with such large borders so closely attached to the large initials on all four sides is not commonly seen in illuminated manuscripts. Also, we have two large initials but no other text, so we start asking questions about what happened to these objects and how and why such images came to look the way they do today. At this point we have to start looking ‘beyond’ the image, at the materiality of the object: what is it made of and how can we explain the size and composition of the images?

Conservator’s approach

Last year MS 293a arrived at the conservation studio because it needed some treatment. The fragment was lined with cardboard which was acidic and causing tensions in the parchment. Both of these features were damaging the object.

When MS 293a arrived at the conservation studio I followed the usual starting procedure of figuring out what I was dealing with. The catalogue description of the object gave me a good idea of the date of the illumination fragment and its iconography, but very little was written about its materiality.

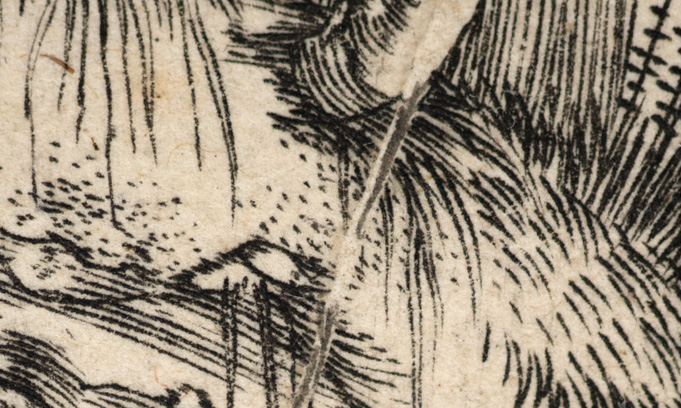

Using raking light was the most effective observation method to understand the composition of the object. We can see the texture of the surface, giving information about the thickness of the paint layers and the way gold was applied. Raking light also highlights the presence of separate pieces of parchment. So not only is this a fragment from an illuminated manuscript, but it is an assemblage, a collage of several fragments. This explains the very complex completed image, acting as an individual painting.

Cutting illuminated manuscripts to create new ‘beautiful’ images was a fairly common practice in the 19th century and demonstrates the changing attitudes towards illuminations over time. Mid-19th century revival of interest in Gothic art led to the invasive exploitation of illuminated manuscripts where illuminations were cut and reused in a different context and format: MS 293a was assembled to stand as a painting. It is, as Stella Panayotova writes in the catalogue of the COLOUR exhibition, “a damage inflicted upon illuminated manuscripts, motivated paradoxically, by admiration for them as works of art”.

Backing removal

As mentioned before, the collage was supported by an acidic cardboard. It had been glued with animal glue and stuck firmly onto the board.

The illuminated cutting is painted on parchment which is made of animal skin and is both a very durable but also very reactive material. Parchment becomes stiff over time and reacts hugely to the relative humidity of the surrounding air so tensions can appear when the parchment is forced into a certain shape. My task was to remove the backing and mount the object to keep it safe and stable.

I had to remove the backing board layer by layer in order to reduce the risk of distorting the illumination which could disturb the paint layers. During the process the collage was laid onto a large piece of felt so that the illumination was not crushed. A thin layer of paper was found at the back of the collage and was probably the sheet of paper on which the pieces of the collage were originally adhered. We decided to leave it in place in case removing it would loosen the pieces. However, getting so close to the back of the illumination was intriguing so we looked at the object with transmitted light (now that it was fairly thin) and were able to make out large black Gothic letters. These letters are written on the back of the initial fragment. This was a magical moment and confirmed that the initial belonged to a very large manuscript.

We had already so much information and could be fairly confident in attributing the illuminated initials to a Choir Psalter, written in Latin and originating from Avila in Spain in the late 15th century.

We also found out via observations under natural light and raking light that the collages were made of 8 fragments (MS293a) and 3 fragments (MS293b) respectively. Our curator was fairly confident in attributing the floral borders to the same illuminated manuscript as the initials. We could now go further in our understanding of the object and being able to reveal how the ‘artist’ who made the collage achieved the final composition. This is where our research scientist comes in.

Scientific approach

Collaboration with Dr Paolo Romano and Claudia Caliri from the LANDIS Laboratory in Catania (LNS-INFN and IBAM-CNR), allowed us to analyse MS 293a with a cutting-edge macro-XRF scanner, which they shipped here all the way from Italy! The spectral images obtained were interpreted by our research scientist and here is what they revealed:

The elemental map for iron (Fe-K) shows the presence of iron in various areas. The obvious place where we can see iron is in the gilded areas because iron is a constituent of Armenian bole, which would have been used as the ground layer for the application of gold leaf. However, we can also see what appear to be letters throughout the centre of the image. By flipping the image over (see image below) and adjusting its contrast we realise that these are indeed letters, written in iron-gall ink on the other side of this parchment page. Careful observation allows us to start reading the text hidden behind the collage.

The false-colour elemental map for zinc, chromium and cobalt (in red, green and blue, respectively) reveals the presence of elements, all of which are characteristic of ‘modern’ pigments. Combining this information with other analytical data, we can identify the presence of zinc white, cobalt blue, barium chromate and a chromium-based green, all of which were first manufactured in the first half of the 19th century. This information, together with the absence of any pigments manufactured after 1850, suggests that the collage was assembled, and the image retouched, probably in the 1840s, in line with the 19th-century practice of excising illuminations from manuscripts to create new art objects.

Conclusion

Collaboration between curator, scientist and conservator helped to retrace the origins and the story of these collages and to document them. These objects are new valuable objects, made of ancient valuable fragments. We won’t undo the collages because they document historic practice on top of being a new artwork. Besides, there is currently no parent manuscript so re-uniting the fragments is not possible – and if it was, digital methods could allow us to reunite fragments from all over the world by use of online digital tools, for example the IIIF (International Image Interoperability Framework). Separating the pieces could also damage the parchment and the paint layers, and having individual fragments without a specific place or use for them wouldn’t be appropriate.

Revealing the truths of an object is so important because we can’t undo what has been done for various reasons explained previously. However, we can document the object and share the information. One day, perhaps, through sharing information, we will find more related fragments that will feed into our understanding of the object itself and the historical practices involved and we may even be able to start reconstructing the illuminated manuscript that was once proudly standing in the Royal Monastery of St Thomas in Avila.

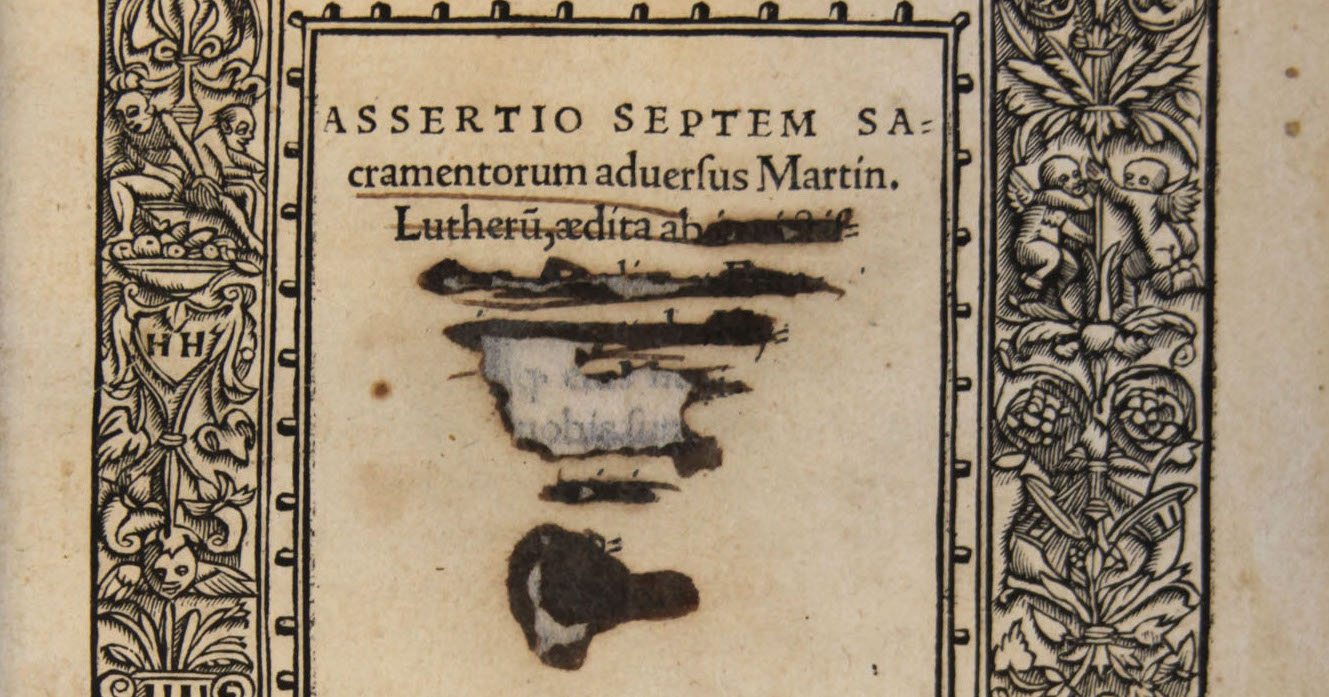

This cutting from our collection gives an idea of the scale of a Choir Plaster and how the fragments of the collage could have been laid out on a page. This is MS 197, from a 15th-century Italian Choir Book. We can see the large initial, the floral borders, the coat of arm and large black manuscript letters.

With special acknowledgement to Dr Paola Ricciardi, Fitzwilliam Museum’s Research Scientist, for her input with scientific research and imaging and for her help with co-writing this blog post.