Work Placement at the Manuscripts and Printed Books Conservation Studio

Jessica Phipps Wardle

November 20, 2017

Manuscripts and Printed Books

Tags: architectural plans, bookbinding, case binding, founder's library, hamilton kerr institute, rebacking, sealing machine, student, ultra-sonic spot welder, work placement

In the summer I spent four brilliant weeks with the conservation team in Manuscripts and Printed Books. Edward, Gwendoline and all the staff at the Fitzwilliam generously gave their time and knowledge to make my placement at the Museum enjoyable and an invaluable experience as part of the MA conservation course that I am studying at Camberwell College of Art. I completed a number of practical projects, including rebacking of cloth case bindings and the repair of architectural plans of the Founder’s Library.

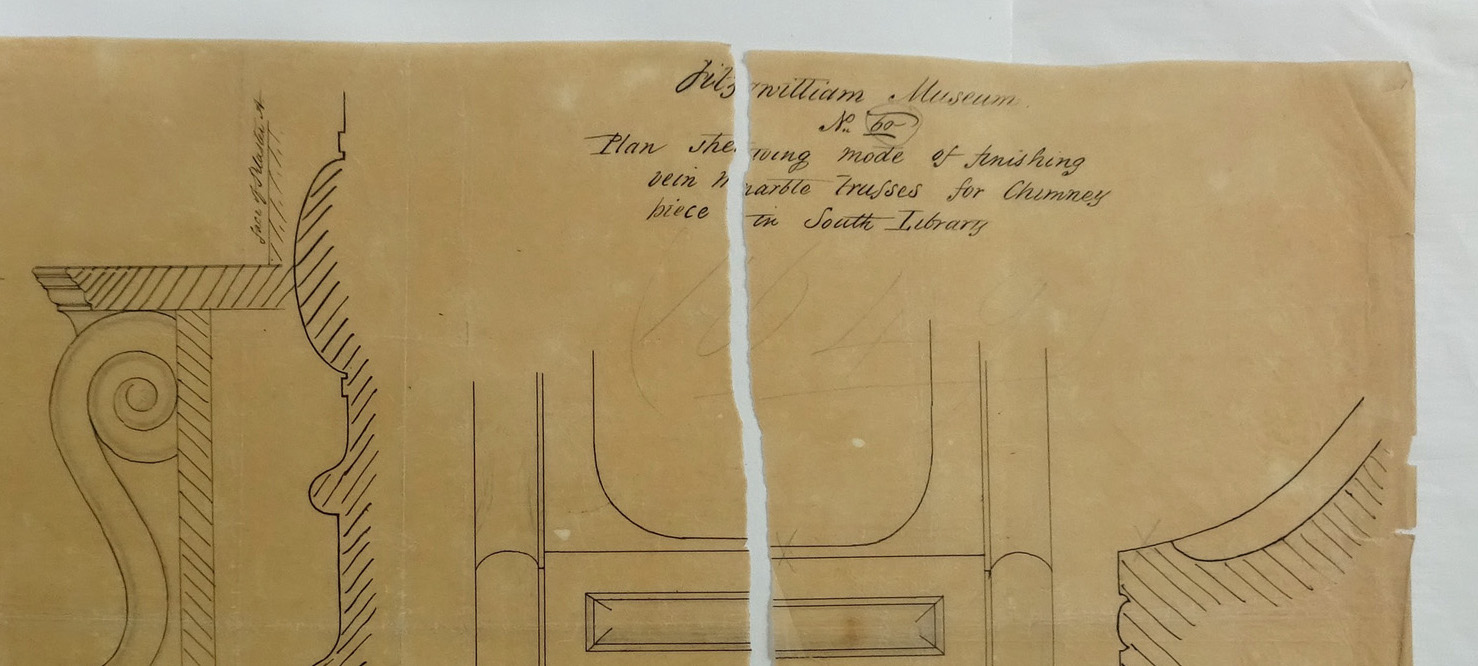

The architectural plans, mostly from 1847, were graphite and pen and ink on drafting paper – a transparent paper made by adding oil which, after many years, has degraded to make the drawings very fragile and brittle. This was a satisfying collection to work on as the drawings were taken off poor-quality backing paper, carefully flattened, and repaired with fine Japanese handmade paper. Finally, to make them easier to handle and visible on recto and verso, individual folders were made from Melinex®, an archival polyester film. For this I also got to learn to use some new pieces of equipment – the polyester sealing machine and ultra-sonic spot welder. With these I was able to make folders around the object, as you can easily seal as many sides around the enclosure as you need. It meant I could also get a wide enough border to prevent the corners of the drawings from being damaged in future. The ultra-sonic spot welder allows the old label to be displayed alongside the drawing in the same folder without the need for attachment to the Melinex®.

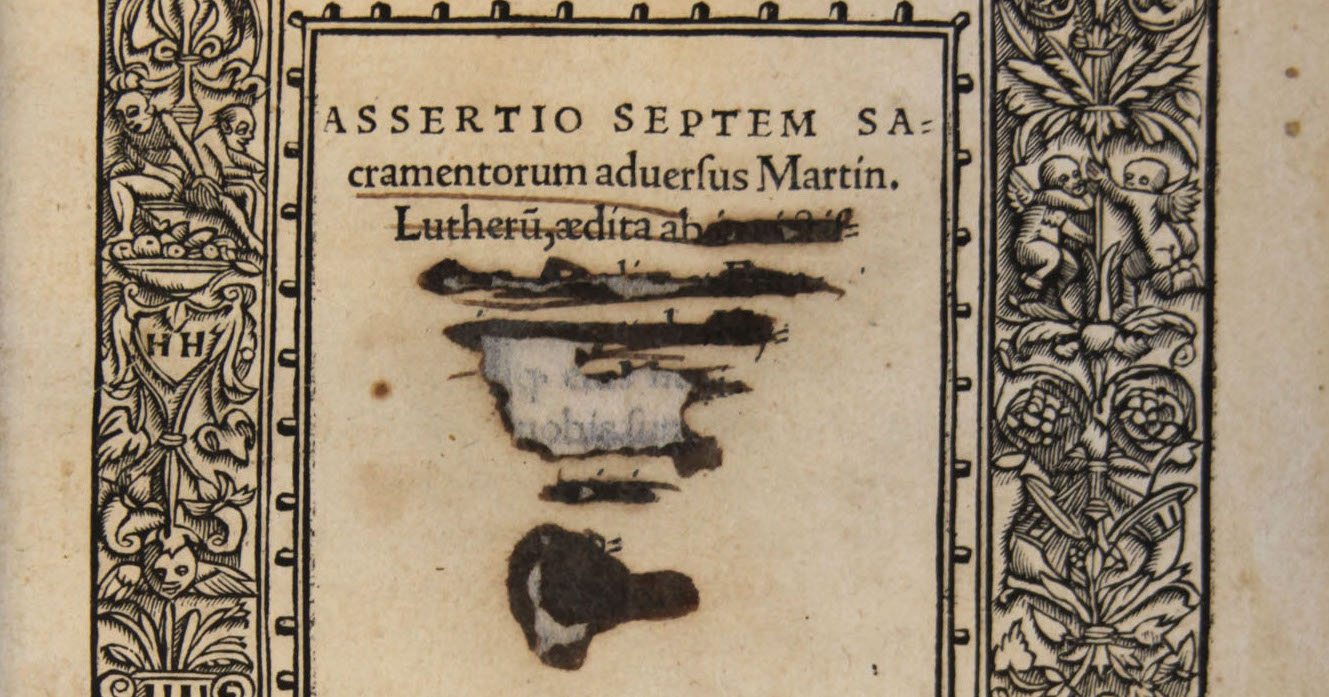

The Founder’s Library at the Fitzwilliam holds a wide variety of different bindings on rare examples of manuscripts and printed books. The cloth case binding rebacks I completed were for two volumes of the Arabian Nights Entertainment and an edition of Augustinus printed in 1490. Although all three bindings were nineteenth-century cloth case bindings, the damage and therefore the conservation treatment were each unique. I like the problem-solving element in taking a similar technique of creating a hollow-back binding to give durability and allow for the original spine to be put back in place, but taking different approaches depending on how he original structure was damaged and how that dictated access into the structure for repair with minimal disturbance to each binding. For instance, Volume II of the Arabian Nights had spilt endpapers making this an entry point to the spine whereas the endpaper joints in Volume I were in good condition so it was important to not damage these during treatment – access was through the spilt down the length of the cloth joint. The Augustinus had a whole piece of the spine detached and revealed a piece of printed paper used as a spine-lining that it was important to keep and protect in case it holds information worth future investigation.

Being in the studio meant that during the four weeks I was able to observe and learn from the diverse range of conservation treatments going on. Work on parchment was a new technique and material for me so I enjoyed being able to have a go at reproducing some historic and current repair processes. The area of printed books and manuscripts encompasses a range of different materials and techniques, with the additional consideration that bindings need to ‘work’ mechanically every time the volumes are consulted. I started a model example of a herringbone sewing: making this really helped me to understand how sewing on double cords works and locks each stitch in place for a very strong and flexible structure. As well as being ‘working’ objects, books and manuscripts are artefacts that need looking after and handling with respect. I think one of the factors in helping communicate this is the beautifully handcrafted bespoke cases and boxes made for items in the collection. The books need to fit exactly to protect them. The clam-shell box I made has double thickness on the walls making them very strong; lined with conservation board, they create a non-damaging environment within.

What made my placement particularly enjoyable was all the people who took the time to show me around and share their knowledge. I am grateful to have had the opportunity while in Cambridge to visit the wider conservation community there, from current students, Anna and Elisabeth, giving me a tour at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, to Jim and the team at the University Library showing me the many and varied conservation projects that they have going on, and to Bridget, Françoise and Claude at the Cambridge Consortium and Nicholas Bell at the Wren Library, Trinity College. I found the diversity of different projects being undertaken in all the conservation studios and treasures held in the collections fascinating.

Each of the departments at the Fitzwilliam also took time to show me the different projects that they have ongoing and their collections, from which a lot of exciting research is generated. It was good to see something of the day-to-day work of departments dealing with new acquisitions, items for loan and exhibition and challenges of storage and building constraints as well. I learnt a lot, and will continue to do so through my final year of study and beyond.

Finally I’d like to thank Edward Cheese and Gwendoline Lemée for making it an absolute pleasure to be in the conservation studio and taking the time to teach me many new skills. The experience went far too fast!